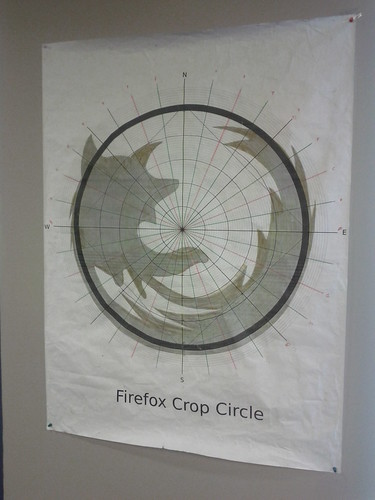

Here at Mozilla, we take pride in our community -- it is the number one reason that Firefox is awesome. One great community project in the past was the Firefox Crop Circle. This is a (the?) blueprint that was used to make the project happen, and we show it off on one of our office walls, not far from my desk, where I see it every day.

Under the Hood of Firefox Input

Note: Several people asked where the link is to actually add feedback to the site. This is, of course, a good point. As mentioned in the comments: The designated entry point for the feedback application is going to be an extension bundled with Firefox 4 Beta. For more information, please read Aakash's blog post. To try out the application already, feel free to add happy or sad feedback to the test site.

This morning, we published the Firefox Input application. It is a little web application soliciting feedback from our Firefox Beta Program users. The aim is to make it as easy as possible for people to tell us what specifically they like or dislike about an upcoming version of Firefox.

The application was, as far as software goes, developed very rapidly: We made it from requirements to production in a mere three weeks. What made this possible was a number of reusable components that allowed us to avoid reinventing the wheel and stay focused on making the application awesome.

A few key components of the Input application:

- Django. I can't stress this enough, but Django is a fantastic web application framework. It makes it incredibly easy to set up a web application quickly and securely. Their built-in admin pages save me days of work that I would otherwise have to spend to allow project admins to edit the application data.

- Jinja2 and Jingo. The only big drawback of Django is its template language: The instant you make nontrivial web applications, it gets in your way. Luckily, like all parts of Django it is replaceable: Jinja2 and Jeff Balogh's jingo interface comes to the rescue. The two of them are already in use over at AMO and also serve us well on Input.

- Term extraction. Firefox Input extracts key words from all feedback. Sure, you can just split the sentences into words, but if you want to avoid collecting all sorts of meaningless particles ("the", "a", "if", ...), it becomes a little more complicated. We are using the topia.termextract library, which gladly does the heavy lifting for us. Only caveat: It only works for English, so once the application is localized, we need a different solution for the other languages.

- Search. For the longest time, there was no generic way to do search in a Django app (other than straight SQL queries). In the meantime, haystack has started to fill that gap. We use it on Input in conjunction with Whoosh, a pure-Python search library. That is very easy to set up, at the expense of scalability -- if we outgrow it, however, it will be easy to switch search engines with virtually no code changes at all. Thumbs up!

- Product details. Only very recently we released a Mozilla product details library for Django, and this is the first application to rely intimately on up-to-date product data: Input only lets users of the latest beta versions of Firefox add feedback, so it auto-updates its product data periodically to gather feedback for the newest versions as quickly as possible.

As always, the source code of Firefox Input is openly and freely available. If you notice any problems with it, feel free to fork it on github, or file a bug in our bug tracker.

What happens when you click the Firefox download button?

Everybody knows Mozilla makes Firefox. But there is a lot more software at work here at Mozilla that you might not be aware of. For example: What happens when you go to getfirefox.com and click on the download button?

By clicking on the button, you ask our servers to send you a specific file, for example: Firefox 3.6.3, for Windows, in German. On a small website, the server would just fetch the file and hand it to you. But if you need to handle millions of downloads a day like we do, a single server can't handle it all by itself, so it gets more complicated. In order to provide you with downloads, updates, etc., as fast and conveniently as possible, Mozilla collaborates with a number of mirror providers that have volunteered to host Firefox and other downloads on our behalf, thus sharing the load of our numerous downloads between a number of servers all over the world.

By clicking on the button, you ask our servers to send you a specific file, for example: Firefox 3.6.3, for Windows, in German. On a small website, the server would just fetch the file and hand it to you. But if you need to handle millions of downloads a day like we do, a single server can't handle it all by itself, so it gets more complicated. In order to provide you with downloads, updates, etc., as fast and conveniently as possible, Mozilla collaborates with a number of mirror providers that have volunteered to host Firefox and other downloads on our behalf, thus sharing the load of our numerous downloads between a number of servers all over the world.

For some years now, we have been running a bundle of software called "Bouncer" to handle our downloads for us.

Bouncer consists of of three components: The user-facing bounce script, an administrative interface called Tuxedo, and a mirror checker called Sentry.

First, the bounce script. It is the only component the "ordinary user" gets to interact with. It essentially does the following after you click on a download link:

- It determines if the product you asked for exists.

- Out of our list of mirrors, it picks one that has your file. Initially, it would pick one at random. Over the years, the logic has become more elaborate though: Meanwhile, it takes into account in what country you currently are, as well as how strong the mirrors are (stronger mirrors serve more downloads, weaker ones serve less).

- A split-second later, Bouncer refers you to the server it decided on, and that server will send you the file you asked for.

But wait, there is more! How does Bouncer know what products are available, for what operating systems, and in what languages? That's where the admin interface comes in. We have a release engineering team who work hard every day to deliver the newest software versions to you in handy little packages. Previously, during every release, an engineer would manually tell Bouncer that a new version was available for download. But just last week, we improved this process by introducing a new interface to Bouncer, with a project called Tuxedo. The release engineering team can now, fully automatically, feed new versions into Bouncer at the time of release, with no manual intervention. With less time spent on repetitive tasks, we can spend more time making Firefox awesome.

Finally, the Sentry component is a script that periodically checks the health of our mirrors, and adjusts our settings accordingly. This is to ensure that a situation where you are forwarded to a mirror that is currently unavailable is very, very rare. So far, these mirror checks happen from Mozilla Headquarters, and therefore reflect the connectivity we get to the mirrors from here. In the future, we want to improve that by taking into account more how our users' connectivity is to the specific mirrors (for the geeks out there: Network proximity != geographical proximity), which has the potential to result in faster download times, less expenses for mirror providers, and general happiness.

As you can see, there are a lot of things happening behind the scenes before Firefox makes its way onto your computer at home, and we are constantly working on improving the way we are doing things. Plus, as always: Bouncer is completely open source, and we have a public bug tracker, so if you notice any problems or see room for improvement, make sure to let us know.

Photo credit: "directions", CC-by licensed by Phillie Casablanca.

On Hackability

There is a Belorussian version of this article provided by PC.

One of the talks I really enjoyed at recent FOSDEM was Paul and Tristan's presentation on Hackability. (Tristan uploaded the English slides to slideshare, as well as the French ones).

One of the talks I really enjoyed at recent FOSDEM was Paul and Tristan's presentation on Hackability. (Tristan uploaded the English slides to slideshare, as well as the French ones).

Essentially, it was a great promotion for keeping the Web (and Firefox as the tool we view it through) (both legally and technically) open, its building blocks visible and interchangeable. If you can't open it, you don't own it.

As a result, this also means the "view source" function is not there to feed the user's idle curiosity, it is a vital and irreplaceable part of the Web. Likewise, a tool like Firebug does not exist to "break" other people's websites. Instead, it helps us to use the web the way it was meant to be used.

Recently, a colleague of mine (don't remember who, sorry) linked to a little website called patch culture.org, that, in spite of its simple appearance, promotes exactly that: using the Web the way it was meant to be used, fixing, improving the Web on our way through other people's sites, and better yet, share our changes with the people who own the sites. Their steps are easy: 1) Install Firebug, 2) change a website, 3) email a patch to the owner.

Sounds easy (to geek ears, anyway) but is harder than it looks. For starters, how do I get my changes out of Firebug? It's a concept we could call "diffability". If I have to write a book describing what I did to some website's DOM nodes and CSS rules, I am far less likely to fix someone else's website for them than when there is an easy way for me to do it. Granted: Even if Firebug let me export a unified diff, owners of non-trivial, framework-based web sites wouldn't be able to just go ahead and apply it on their codebase. However, diffs are human engineer readable. Without losing a ton of words, the website owner could look at the changes I made and choose to apply them to their software in the appropriate spots.

![]() Second, how do I make my changes stick? We Open Source developers are of course some of the more altruistically inclined citizens of the Web, still if you are going to fix someone's website, you are likely to do so to lower your own annoyance level first, then everybody else's. Therefore, you want your changes to "stick", if or if not the website owner decides to accept and deploy your changes.

Second, how do I make my changes stick? We Open Source developers are of course some of the more altruistically inclined citizens of the Web, still if you are going to fix someone's website, you are likely to do so to lower your own annoyance level first, then everybody else's. Therefore, you want your changes to "stick", if or if not the website owner decides to accept and deploy your changes.

Thankfully, this is achievable, though it involves a little bit of a hassle. There are add-ons out there, most notably Stylish (for CSS-based changes) and Greasemonkey (for JS-based changes). These two were recently joined by Jetpack Page Mods. While Greasemonkey is a solid platform with tons of contributions, I see its biggest flaw in missing a solid standard library that takes the pain out of JavaScript, a problem Jetpack mitigates by shipping with jQuery included. In comparison, using jQuery with Greasemonkey is many things, none of which is "beautiful". If Greasemonkey wants to stay the technology of choice for "web hackers", it needs a standard library. Only then will it fill its place as a lightweight extension engine in the future, (yes, in spite of its recent inclusion in Chrome). It would be a twisted situation if it became easier to write full-blown (Jetpack-based) extensions than writing a user script. It's the reason I am already writing small website changes as Jetpacks and not GM scripts, and I am not the only one. But because competition is good for business, on the Web as much as elsewhere, I hope the Greasemonkey guys stay on top of their game.

In summary:

- Let's make and keep the Web open and hackable!

- We can change web sites, but it's hard to share what we did. A great way towards more open hacking would be a diff engine in Firebug. Even if it only exports pseudo-diffs, or even if the diffs can't be applied with one click unless you run a fully static website.

- Finally, it's possible but hard to make changes stick. Greasemonkey is a strong contender in the field, but if they want to keep being the number one "hackability engine", they'll need to make writing scripts easier by adding a decent standard library. After all, it is not the 20th century anymore.

Firefox 3.6 RC1

The Firefox 3.6 Release Candidate 1 has been released and its new features are just fantastic! From the first-run page:

- Select a new persona from the Personas Gallery.

- More than 75% of Add-ons work. Test your favorites!

- Try watching a video in full screen mode.

- Have you seen websites using WOFF fonts?

- Kick the tires with improved JavaScript performance, browser responsiveness, and startup time.

- See the release notes for more details.

Go check it out.

Firefox on the Coliseum

This photo is not photoshopped:

The Mozilla Italia team projected a Firefox wordmark onto Rome's most famous landmark -- and on many other places all over the city. Make sure to check out the picture in its full glory over on flickr.

Picture CC by-sa licensed by nois3lab on flickr.

Firefox 3.5 Released

shadow boxing with -moz-box-shadow

This is another cross-post of an article I wrote for the hacks.mozilla.org blog. It shows off some of the fun stuff web developers can do with the -moz-box-shadow feature that will be released as part of Firefox 3.5.

Another fun CSS3 feature that's been implemented in Firefox 3.5 is box shadows. This feature allows the casting of a drop "shadow" from the frame of almost any arbitrary element.

As the CSS3 box shadow property is still a work in progress, however, it's been implemented as -moz-box-shadow in Firefox. This is how Mozilla tests experimental properties in CSS, with property names prefaced with "-moz-". When the specification is finalized, the property will be named "box-shadow."

How it works

Applying a box shadow to an element is straightforward. The CSS3 standard allows as its value:

none | <shadow> [ <shadow> ]*

where <shadow> is:

<shadow> = inset? && [ <length>{2,4} && <color>? ]

The first two lengths are the horizontal and vertical offset of the shadow, respectively. The third length is the blur radius (compare that to the blur radius in in the text-shadow property). Finally the fourth length is the spread radius, allowing the shadow to grow (positive values) or shrink (negative values) compared to the size of the parent element.

The inset keyword is pretty well explained by the standard itself:

if present, [it] changes the drop shadow from an outer shadow (one that shadows the box onto the canvas, as if it were lifted above the canvas) to an inner shadow (one that shadows the canvas onto the box, as if the box were cut out of the canvas and shifted behind it).

But talk is cheap, let's look at some examples.

To draw a simple shadow, just define an offset and a color, and off you go:

-moz-box-shadow: 1px 1px 10px #00f;

(Each of the examples in this article are live examples first, followed by a screen shot from Firefox 3.5 on OSX).

Similarly, you can draw an in-set shadow with the aforementioned keyword.

-moz-box-shadow: inset 1px 1px 10px #888;

With the help of a spread radius, you can define smaller (or bigger) shadows than the element it is applied to:

-moz-box-shadow: 0px 20px 10px -10px #888;

If you want, you can also define multiple shadows by defining several shadows, separated by commas (courtesy of Markus Stange):

-moz-box-shadow: 0 0 20px black, 20px 15px 30px yellow, -20px 15px 30px lime, -20px -15px 30px blue, 20px -15px 30px red;

The different shadows blend into each other very smoothly, and as you may have noticed, the order in which they are defined does make a difference. As box-shadow is a CSS3 feature, Firefox 3.5 adheres to the CSS3 painting order. That means, the first specified shadow shows up on top, so keep that in mind when designing multiple shadows.

As a final example, I want to show you the combination of -moz-box-shadow with an RGBA color definition. RGBA is the same as RGB, but it adds an alpha-channel transparency to change the opacity of the color. Let's make a black, un-blurred box shadow with an opacity of 50 percent, on a yellow background:

-moz-box-shadow: inset 5px 5px 0 rgba(0, 0, 0, .5);

As you can see, the yellow background is visible though the half-transparent shadow without further ado. This feature becomes particularly interesting when background images are involved, as you'll be able to see them shining through the box shadow.

Cross-Browser Compatibility

As a newer, work-in-progress CSS3 property, box-shadow has not yet been widely adopted by browser makers.

- Firefox 3.5 supports the feature as

-moz-box-shadow, as well as multiple shadows, theinsetkeyword and a spread radius. - Safari/WebKit has gone down a similar route as Firefox by implementing the feature as

-webkit-box-shadow. Multiple shadows are supported since version 4.0, while neither inset shadows nor the spread radius feature are supported yet in WebKit. - Finally, Opera and Microsoft Internet Explorer have not yet implemented the box shadow property, though in MSIE you may want to check out their proprietary DropShadow filter.

To achieve the biggest possible coverage, it is advisable to define all three, the -moz, -webkit, and standard CSS3 syntax in parallel. Applicable browsers will then pick and adhere to the ones they support. For example:

-moz-box-shadow: 1px 1px 10px #00f;

-webkit-box-shadow: 1px 1px 10px #00f;

box-shadow: 1px 1px 10px #00f;

The good news is that the box-shadow property degrades gracefully on unsupported browsers. For example, all the examples above will look like plain and boring boxes with no shadow in MSIE.

Conclusions

The CSS3 box-shadow property is not yet as widely available in browsers (and therefore, to users) as, for example, the text-shadow property, but with the limited box shadow support of WebKit as well as the full support provided by Firefox 3.5 (as far as the current status of the feature draft is concerned), more and more users will be able to see some level of CSS box shadows.

As a web developer, you can therefore use the feature, confident that you are giving users with modern browsers an improved experience while not turning away users with older browsers.

Further resources Documentation

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en/CSS/-moz-box-shadow

- http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css3-background/#the-box-shadow

Examples

stylish text with the CSS text-shadow property

This is a cross-post of an article I wrote for the hacks.mozilla.org blog. It shows off some of the fun stuff web developers can do with the text-shadow feature that will be released as part of Firefox 3.5.

The text-shadow CSS property does what the name implies: It lets you create a slightly blurred, slightly moved copy of text, which ends up looking somewhat like a real-world shadow.

The text-shadow property was first introduced in CSS2, but as it was improperly defined at the time, its support was dropped again in CSS2.1. The feature was re-introduced with CSS3 and has now made it into Firefox 3.5.

How it Works

According to the CSS3 specification, the text-shadow property can have the following values:

none | [<shadow>, ] * <shadow>,

<shadow> is defined as:

[ <color>? <length> <length> <length>? | <length> <length> <length>? <color>? ],

where the first two lengths represent the horizontal and vertical offset and the third an optional blur radius. The best way to describe it is with examples.

We can make a simple shadow like this, for example:

text-shadow: 2px 2px 3px #000;

(All of the examples are a live example first, then a picture of the working feature — so you can compare your browser’s behavior with the one of Firefox 3.5 on OSX)

If you are a fan of hard edges, you can just refrain from using a blur radius altogether:

text-shadow: 2px 2px 0 #888;

Glowing text, and multiple shadows

But due to the flexibility of the feature, the fun does not stop here. By varying the text offset, blur radius, and of course the color, you can achieve various effects, a mysterious glow for example:

text-shadow: 1px 1px 5px #fff;

or a simple, fuzzy blur:

text-shadow: 0px 0px 5px #000;

Finally, you can add ”more than one shadow”, allowing you to create pretty “hot” effects (courtesy of http://www.css3.info/preview/text-shadow/ css3.info):

text-shadow: 0 0 4px white, 0 -5px 4px #FFFF33, 2px -10px 6px #FFDD33, -2px -15px 11px #FF8800, 2px -25px 18px #FF2200

The number of text-shadows you can apply at the same time in Firefox 3.5 is — in theory — unlimited, though you may want to stick with a reasonable amount.

Like all CSS properties, you can modify text-shadow on the fly using JavaScript:

Performance, Accessibility and Cross-Browser Compatibility

The times of using pictures (or even worse, Flash) for text shadows on the web are numbered for two reasons:

First, there are significant advantages to using text instead of pictures. Not using pictures saves on bandwidth and HTTP connection overhead. Accessibility, both for people who use screen readers and search engines, is greatly improved. And page zoom will work better because the text can be scaled instead of using pixel interpolation to scale up an image.

Second this feature is largely cross-browser compatible:

- Opera supports text-shadow since version 9.5. According to the Mozilla Developer Center, Opera 9.x supports up to 6 shadows on the same element.

- Safari has had the feature since version 1.1 (and other WebKit-based browsers along with it).

- Internet Explorer does not support the text-shadow property, but the feature degrades gracefully to regular text. In addition, if you want to emulate some of the text-shadow functionality in MSIE, you can use Microsoft’s proprietary ”Shadow” and ”DropShadow” filters.

- Similarly to MSIE, when other, older browsers do not support the feature (including Firefox 3 and older), they will just show the regular text without any shadows.

A caveat worth mentioning is the ”drawing order”: While Opera 9.x adheres to the CSS2 painting order (i.e., the first specified shadow is drawn at the bottom), Firefox 3.5 adheres to the CSS3 painting order (the first specified shadow is on top). Keep this in mind when drawing multiple shadows.

Conclusions

text-shadow is a subtle but powerful CSS feature that is — now that it is supported by Firefox 3.5 — likely to be widely adopted across the web in the foreseeable future. Due to its graceful degradation in older browsers, it can safely be used by developers and will, over time, be seen by more and more users.

Finally, some words of wisdom: Like any eye candy, use it like salt in a soup — with moderation, not by the bucket. If the web developers of the world overdo it, text-shadow may die a short, yet painful death. It would be sad if we make users flinch at the sight of text shadows like typography geeks at the sight of “Papyrus”, and thus needed to bury the feature deeply in our treasure chest.

That being said: Go try it out!

Further resources

Documentation

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en/CSS/text-shadow

- http://www.quirksmode.org/css/textshadow.html

- http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-text/#text-shadow

Examples

World's Fastest Cup Stacker

This kid is awesome:

He's 11 years old, and the world's fastest cup stacker. He made this "Fastest Firefox" video for the upcoming Firefox 3.5 launch. Of course Firefox can't stack cups, but its new TraceMonkey JavaScript engine is also one of the fastest in the world!